‘Huh? Heart knowledge? That doesn’t exist

right? Lolz’

‘I don’t know how to define that… is that

where you get all the virtues like compassion, and charity?’

‘It’s the subjective experience right?

Emotions and opinions that we have on God?’

Scarily enough, these are some of the

answers that I got when I asked youth to define the term, ‘heart knowledge’.

Head knowledge and heart knowledge are

favourite terms of catechists and adults in charge of formation and the like. I

always hear them getting thrown around. You know, ‘David, you have too much

head knowledge. You need to learn more heart knowledge!’? Well, actually, no, I

don’t know. These terms have actually caused me much angst for a very long time

now, because, 1) they are extremely vague and ambiguous terms, so I have spent

quite some time trying to figure what they mean, and 2) growing up as an

impulsive nerdy teenager, I obviously read a lot and acquired a lot of ‘head

knowledge’.

As a confused youth, I went through several

phases where I was confused about the terms and just nodded to trying

unsuccessfully to ditch ‘head knowledge’, to trying unsuccessfully to ditch

‘heart knowledge’ in a reactionary manner, to finally finding peace after

dropping the concept totally for one with clearer and well defined terms. It

should be interesting to note that, as someone who has read books and extracts

of Catholic teaching fairly decently across the history of the Holy Mother

Church’s two thousand history, such terms where never employed until the last

fifty years, and then, mostly in evangelical protestant circles. They’re

essentially new age fluff as my theologian/teacher mentor calls it.

|

| It tastes good, it sound good, but no one is sure about what it is. |

Ambiguity

The ambiguity of terms is a great cause for

concern and as a pseudophilosopher and student of science, I do not like

ambiguous terms at all. While, head knowledge is easy enough to define, and is 'limited' to the theoretical knowledge or reason that one attains through reading

and so on, often these are concrete concepts like ‘Jesus Christ was crucified

for our sins.’, however, ‘heart knowledge’ is much more difficult to define. It

is anything from between, ‘practical experience’ to ‘feelings and emotions’ to ‘subjective

opinions’, but exclude what is head knowledge (after all, they cannot be the

same in order for a distinction to occur).

Now, each of these three things are very

different and shouldn’t lie under the same umbrella. ‘Subjective opinion’ is

something not unique to ‘heart knowledge’ since it will exist in the realm of

theory as well, thus the terms will overlap, and remain ambiguous.

Next, ‘feelings and emotions’ are not a

good foundation for the faith at all; the church fathers warn that emotions are

fickle and easily manipulated. For example, when we are in the presence of the

Blessed Sacrament, we should not expect to feel anything at all, because the

transubstantiation happens at a level beyond our sensory ability to perceive.

What we look at, smells, tastes, looks and feels exactly like ordinary bread

and wine. Yes, we often feel a supernatural sense of peace in His presence

under the veil of a sacrament, but what happens if all that is taken away, and

we presented with the consecrated host that looks, tastes, feels and smells

like ordinary bread? Well, our mind intellectually reminds us that piece of

bread before is really the body, blood, soul and divinity of Christ hiding

under the appearance of bread. I can imagine several possibilities where one

will not feel this feeling at Mass, for example being in a state of anger or in

a state of distraction. Thus, if one’s foundation of faith is based on

feelings, it will surely fall like the house built on sand. (This is not to say

that there are not emotions involved in our spiritual life. That supernatural

sense of peace that signifies God’s presence is mystical experience, and a

great consolation, but should not be the bar for our faith. Neither does it not

mean that there is only one way to know things, only that not all ways of

knowing things are equal.)

Finally, we are left with ‘practical

experience’, which is only one that provides somewhat of a clear distinction

between knowledge from the Heart and from the Head. However, even here there lies

ambiguity. For example, say, I was meditating on a piece of scripture and was

then granted an epiphany of said passage by God, and felt his supernatural

peace as reassurance, now would that be head knowledge or heart knowledge? It

was certainly a theoretical and reasoned gain of knowledge yet, it was also a

practical experience. Furthermore, the seat of knowledge is the head in western

philosophy and the heart is the seat of emotion. It is from the west that we as

Catholics derive our philosophy. Thus, that is how society has come to view

these terms. No one says, ‘my head is filled with sorrow’ or ‘I have grasped

the theory of relativity in my heart.’ That certainly sounds odd.

Anti-intellectualism

To add to the problem, when heart knowledge

is used in juxtaposition to head knowledge, it is usually taken to mean all

three aforementioned definitions at once, with the further presumption that

intellect is limited to head knowledge. Yet, knowledge is function of the

intellect, in fact, to know something is also act of the intellect (and yes,

there is a difference between knowing and knowledge, whereby the former is a

spiritual/emotional perception of information and the latter an ownership of

information). Thus, I can know Christ in

my heart, but in order to do that, I must have knowledge of Him in my head.

However, this article is not meant to deal

with that epistemology, and I trying to make this as readable as possible, so

we’ll get back onto the real point, the separation and limitation of the

intellect to the ‘head knowledge’. Often, when these terms are used, they are

done so, while probably unwittingly, in an antagonistic fashion. At catechism

classes and retreats, I so often hear the teacher or retreat master say after a

very short and simple lecture, ‘Okay, I think that’s enough head knowledge,

let’s do activity X to use our heart to learn instead.’ or during planning

sessions, ‘that’s too much head knowledge, we don’t want to go too much in

depth, it will fly over their heads.’ Unfortunately, an unintended consequence

of keeping lessons ‘practical’ in such a manner is that the kids then go

through life with the idea and complacency that I don’t actually need to learn

about God, I’m just fine the way I am. Jason T. Adams, a high school theology

teacher, sums it up rather neatly, with my

emphasis:

In the religion

classes at Catholic schools, the academic breakdown and failing interest of the

students is caused by two factors. First, students have been conditioned to

think that faith and reason are opposed. Catechists have coined an expression

that reveals this: "When it comes to faith, I want to teach my students

heart knowledge instead of head knowledge." Contrary to this trite

philosophy, "head knowledge" (a grasp of the tenets of faith), and

"heart knowledge" (the application of understanding to concrete

practices) are not mutually exclusive; rather, they are mutually beneficial and

inextricably related.

The result of this false dichotomy is an attitude in

the students that religion is about feelings, not substance. Because their orientation is non-intellectual from the onset, they

are ill equipped to handle concepts that stretch their minds or call for mental

discipline. The content of faith becomes so subjective to the students that they

believe there are no such things as right or wrong answers to questions of

faith.

You can read the rest here.

Again, that is not to say that these teachers do it on purpose. I firmly

believe it is well intentioned and done as a means of maintaining interest or

not to ‘scare’ the kids off. Moreover, these terms and the conventional way

that they are used appear to my mind to be remnants of the great

anti-intellectual movement of the 1960s. Yes, yes, intellectualism and the

intellect are different things, but it is this general

I-don’t-want-to-use-my-brain attitude that has prevailed and created the

Generation Y and now Generation Z eras of mental laziness and apathy. I had a

dear young friend cheekily remark to me the other day, ‘don’t you ever get

bored talking about intelligent things? Talk about meaningless things, it’s

more fun.’ Personally, I feel this particular attitude is annoying thorn left

in society side, amongst other things, from the hippie revolution in the ‘60s.

|

| Hippism. Bringing the world back to the stone age since 1969. |

Another problem is that catechists don’t

give their teenage students enough credit. In school, by the age of fourteen,

they are learning abstract concepts like trigonometry or photosynthesis. These

things seem rather easy to understand, however try to recall when you were

fourteen trying to grasp the idea that light could be used to split water into

hydrogen ions and oxygen ions and the H+ ions were then used to

power the enzyme that made energy in the body. It probably took you a while,

but you learnt it nevertheless and passed your examination.

Theology is no different, it has terms

which seem foreign when first discovered, but the definitions are memorised and

churned about in the head until an understanding is formed. For example, the

idea of Transubstantiation. It essentially means that the substance or essence

of the bread and wine, that is their ‘breadness’ and ‘wineness’, the things

that make bread and wine, bread and wine, are changed into the substance of

Christ, while the accidentals, the smell, shape, colour, texture, etc caused by

this ‘breadness’ and ‘wineness’ remains. This is certainly not beyond the

average teenager to comprehend, though it will take a bit of time to reflect

upon.

However, all this is not to say that one

should throw the Summa Theologica at young rebellious teenagers. There are of

course different levels of understanding, and the appropriate level should be

taught, however the point is that what is taught should not be watered down and

diluted like a homeopathic therapy.

Devotion

and Theological Thinking

A possible solution to the ambiguity of

head and heart knowledge is simple to drop the terms altogether for something

which is completely concrete and understandable at an instant.

Consider the third definition of head and

heart knowledge, which is the only useable one, that of theoretical and

practical application or experience of theology. Theology, very simply put,

asks the question of if God exists, and He could talk to us, what would He say?

In Christianity, God talked to us, He gave us the Word, and the Word was made

flesh and dwelt among us. So, what did this loving word say? In summary, God

loves you so much that he sent His only Son to die for your sins, now love Him

back with all your being and love your neighbour as yourself.

So how is this translated into theoretical

and practical knowledge? Theoretically, one has to have the knowledge that God

loves you; practically, one has to love God. Thus, to get the knowledge, one

must first learn it and reflect on it, this we call ‘Theological Thinking’.

This knowledge is then put into practice in an act of love towards God, simply

put, a ‘devotion.’

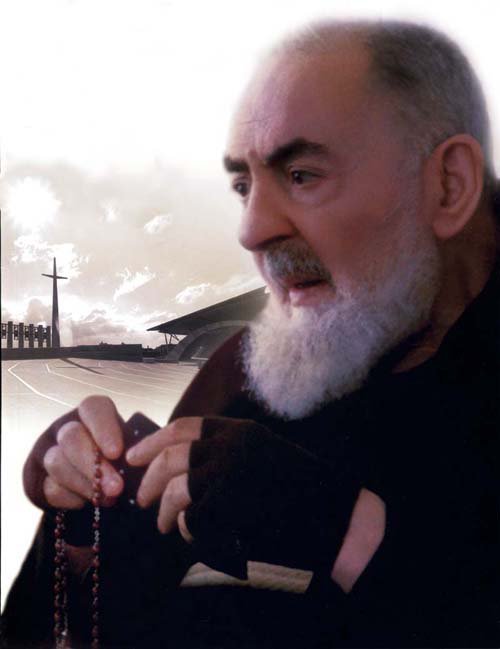

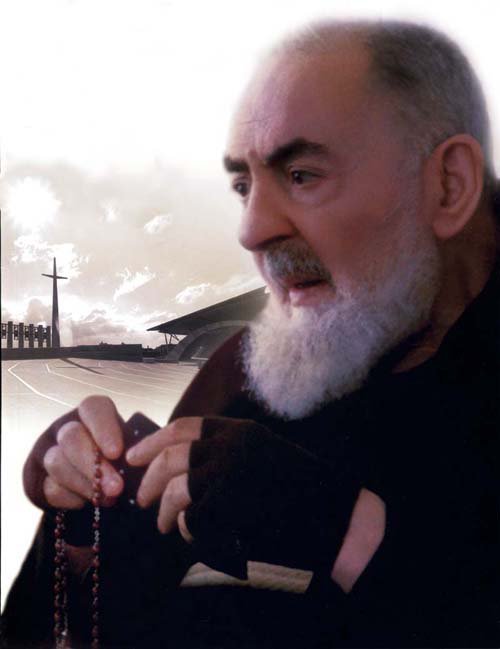

|

The Rosary, both a devotion and contemplation.

Archbishop Fulton Sheen calls it 19 minutes of perfect prayer. |

Recently, after a talk, my priest reminded

us that most people nowadays perform a great deal of devotion but they leave

out theological thinking. He said that the two of them go hand in hand and they

cannot be separated from each other and that absolutely everyone is capable of

some form of theological thinking.

This is certainly true, while not everyone

will reach the same depth of thought, it is more than possible to meditate or

contemplate on the word of God. That is why a church is usually filled with

statues, paintings and stained glass windows that depict saints and various

stories from their lives or from the bible. Together with the priest’s homily

every Sunday, the simple illiterate folk from olden times probably had a much

greater appreciation of theology than we do despite being unable to read.

Intellect

These acts of devotion and theological

thinking are in fact acts of the

intellect. Thus, in an ironic strict sense, ‘heart knowledge’ is ‘head

knowledge’. While knowing God can come through various means, the act of

devotion and theological thinking are both acts of intellect, because one must

will oneself to perform the action. Since they both stem from the intellect,

one cannot separate the practical from the theoretical, so to speak, and one

requires both of them together to nourish the intellect and gain a greater

knowledge of God. True to the both/and mentality of Catholicism, neglecting one

of these acts will result in a stumping of spiritual growth.

This is one of the reasons that the

Pentecostal Renewal movements that spring up megachurches have such high

attrition rates, they are all devotion without any real foundation. The same

can be said for the movements within the church which are influenced by it and

similar groups. ‘Head knowledge’ gives ‘heart knowledge’ its foundation.

However, with ‘head knowledge’ being

eschewed for ‘heart knowledge’ for the last fifty years, most will be found

wanting for even the most basic foundations of the faith to begin some

meditation. Which begs the question, over the last year, how many books on the

faith has one actually read? They don’t strictly have to be theology, but even

books about the lives of saints and spirituality, because if they are good

books, they will spring out from theology. Or even articles online, which are

very easy to find.

Yes, my friends, this very long article was

to inspire you to go pick up a nice good Catholic book. But seriously, the

words we use are important because of the concepts that they hold. You'll be doing what the Holy Father, and all his predecessors have been telling us, LEARN about the faith.